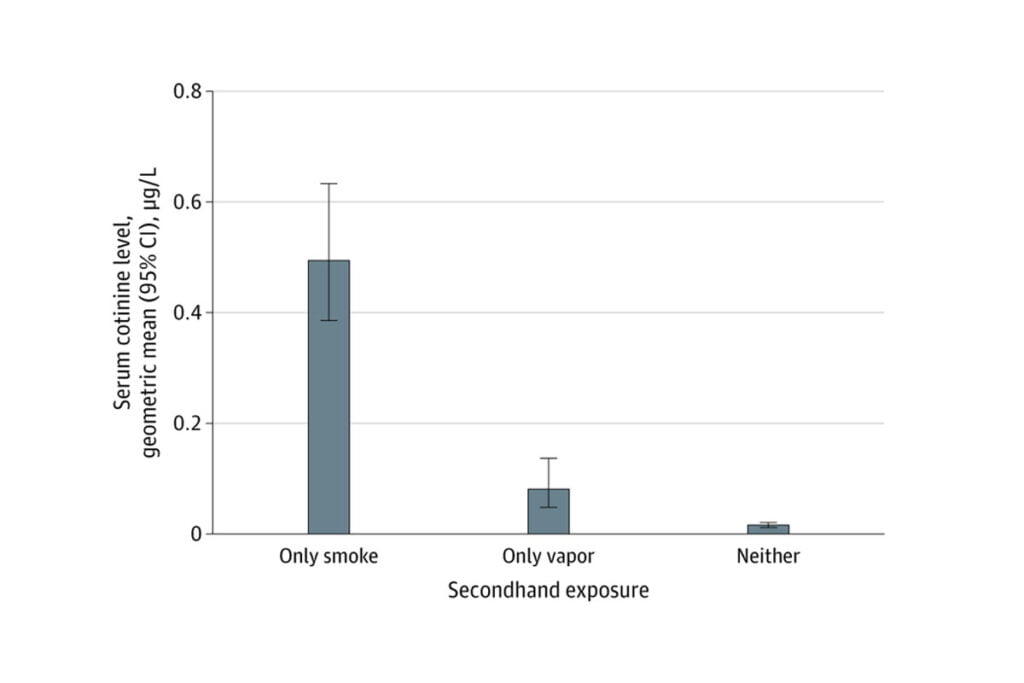

A recent study led by researchers from University College London (UCL), including senior author Professor Lion Shahab, has revealed that children exposed to Vape second-hand vaping indoors absorb significantly less nicotine compared to those exposed to second-hand smoking. The study, published in JAMA Network Open and funded by Cancer Research UK, examined blood tests and survey data from 1,777 children aged three to 11 in the United States.

The research highlights that children exposed to vaping indoors absorb less than one-seventh the amount of nicotine compared to those exposed to indoor smoking. However, children exposed to neither smoking nor vaping absorbed even less nicotine. The study utilized data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected between 2017 and 2020. Blood tests were conducted to measure cotinine levels, a chemical produced by the body after exposure to nicotine, to assess nicotine absorption.

According to Dr. Harry Tattan-Birch, the lead author from the UCL Institute of Epidemiology & Health Care, real-world data shows that nicotine absorption from second-hand vapor is much lower than from second-hand smoking. Professor Shahab echoed this sentiment, stating that concerns about second-hand vaping may be overstated, as second-hand exposure to toxic substances is likely very low.

Implications for Public Health

Despite the lower risk, the study emphasizes that second-hand vaping still exposes children to more harmful substances than no exposure at all. Therefore, it is recommended to avoid indoor vaping around children. The study also underscores the significant risks of smoking indoors around children, which should be avoided at all costs.

The research has important implications for public health policies regarding vaping indoors. While the findings suggest that the health impact on bystanders from vaping is much less than smoking, other factors need consideration when determining whether indoor spaces should be vape-free. Notably, indoor vaping may normalize the behavior, potentially encouraging more people to start vaping and making it harder to quit.

Methodology and Data Exclusion

The researchers focused on children for this study, as they are less likely than adults to have vaped or smoked themselves. This focus ensured that higher nicotine absorption was a result of second-hand exposure only. Two children were excluded from the analysis due to cotinine levels suggesting direct vaping or smoking. Additionally, children exposed to both indoor smoking and vaping were excluded.

The study found that children exposed to indoor vaping absorbed 84% less nicotine than those exposed to indoor smoking. In contrast, children exposed to neither absorbed 97% less nicotine. These findings align with previous laboratory studies indicating that individuals retain 99% of the nicotine produced during vaping, while tobacco cigarettes generate smoke both from exhalation and the lit end.

The researchers suggest that their findings could influence decisions on indoor vaping policies. While the impact of vaping on bystanders’ health appears to be much less severe than smoking, the normalization of vaping behavior and its potential to encourage new users should be carefully considered.

Previous research by the same team indicated that adults in England are more likely to vape indoors than smoke. Data showed that nine out of ten vapers vape inside, whereas only half of smokers smoke indoors. This behavioral trend further emphasizes the need for thoughtful public health policies regarding indoor vaping.

In conclusion, while second-hand vaping poses a lower risk of nicotine absorption compared to second-hand smoking, caution is still advised to protect children’s health. The study’s findings provide a comprehensive overview of the relative risks and inform future public health guidelines on vaping indoors.